“You’re a bigot and a racist!”

Those were the words spoken to me after a speech I made three years ago. They came with not a little vitriol at an otherwise civilized meeting held at the BBC HQ, where about 200 journalists were on hand to discuss the future of media. Considering these words were expressed by a professor holding a Chair at a well-known British school of journalism, you might be tempted to believe him. Hopefully, however, if you know me, you’ll disagree. In any event, I was marked by this public outburst. In many regards, I feel it epitomizes the state of play in media today, where people are quick to jump to un-researched judgments, replete with name-slinging under the banner of a self-attributed self-righteousness. And both sides of the political divide are guilty of this type of behavior. As someone who tends to find himself in the middle ground on many issues, I often encounter relevant arguments on both sides of the aisle. I definitely reject being labelled a leftist or a right winger; even more so the insulting epithets thrown at me by this journalist with a certain repute.

Context is relevant

So, why did this man feel the need to call me by such names? Context is important, so I need to plant the décor. These days it seems we have a penchant for analyzing words, people and events removed from their original surroundings. On this note, I am saddened to see the drop in the study of traditional and military history at universities. Study of History and Philosophy has fallen 17.5% over the last ten years in the UK and the number of students in the US taking a major in History is down 30% over the same period. Coming back to the context of this BBC-hosted event, I was delivering a twenty-minute speech on the future of media with a brief to be provocative. My provocations started with quizzing the room about an article that was featured in the New York Times in May 2018, “Meet the Renegades of the Intellectual Dark Web.” I asked how many of the attendees had heard of a number of organizations, associations and individuals that I deemed pertinent in any discussion about the future of media. These included:

- The Intellectual Dark Web (IDW)

- Professor Jordan Peterson

- Waking Up with (the neuroscientist) Sam Harris

- Claire Lehmann (founder of Quillette)

- Tim Ferriss

- Joe Rogan

- Femsplainers

Don’t be so fast to judge

This professor above clearly felt entitled. He believed that by listening to these people and shows, I must be associated with them. More surprisingly for a journalist, he was quick to judge without really knowing the timbre and content of what is said on these shows. His outburst was much like the tone in the subtitle of the NYT article, written by Bari Weiss, that read “[The IDW] alliance of heretics is making an end run around the mainstream conversation. Should we be listening?” Indubitably, the “institutional” viewpoint was (and probably still is) that the many millions of people listening to and discussing the subjects being addressed by these “heretics” are way off base. Sure the IDW was just a loosely held term to describe these individuals, including most of the list above and others such as the mathematician Eric Weinstein, his brother the biologist Bret Weinstein, author and philosopher Christina Hoff Somers and conservative journalist Douglas Murray. But the very fact that the press was casting such aspersions about individuals that had such a large following was to forget the role of journalists to help make sense of what’s really happening out there. The people and associations I cited were not only NOT a bunch of racists and bigots; and that I was listening to them didn’t and doesn’t mean I necessarily subscribe to what they were saying. I was merely stating that I was seeking to find out what was being said throughout the spectrum of society. Without even deigning to listen to what is being said on these channels, it’s desperately easy to be mistaken about their content. Today, it’s no longer advisable to believe blindly what mainstream media is presenting.

Casting a wider net

The vast majority of the people in the room did not raise their hand. By displaying their lack of familiarity, I was claiming that mass media (as represented by those in the room) is missing out on a whole tranche of discussion and debate, not to mention a burgeoning channel of distribution in the form of podcasting. It smacked of a haughty “all-hail-the-newspaper” thinking. And it certainly was representative of a rather limited view of the world. My premise was that, to be properly equipped for the future, self-respecting journalists have to listen to and learn what is being said and thought by the public. Yes, there’s lots of trashy libellous talk and spam out there. However, there’s an entire audience listening to and discussing alternative viewpoints with a level of debate that we aren’t finding enough of in mass media. I would venture that everyone — across the spectrum — could agree that freedoms of expression, civil liberties and meaningful debate have been widely reduced. We’ve had a confluence of events — social unrest, the pre-eminence of big tech, the pandemic, terrorism and the practice of cancel culture — that have quashed much-needed debate out of our society. We’ve stopped wanting to listen to alternative viewpoints. Call it disruption fatigue or a lack of patience, but we’ve been digging ourselves into a hole and building Maginot lines of indignant and self-righteous sand castles. For anyone versed in the practice of debate, you’ll know it is best to understand deeply the opposition’s stance. As such, it’s advisable to cast a wider net in order to make sure you’re not listening merely within an echo chamber, but are genuinely able and interested to hear the arguments on the other side.

The growth in alternative channels

In the intervening three years since that speech, we’ve seen a further flourishing of new media stations, channels (granted with more or less success) and personalities in many countries. Among the more reputable, in the UK, there’s Unherd with Freddie Sayers and Lockdown Sceptics with Toby Young; FranceSoir TV in France; and Quillette (Claire Lehmann) in the US/Australia. In France, where the top 6 TV stations have seen their audience market share fall from 81% in 2007 to 56% in 2020, the conservative station CNEWS (owned by Canal+) has seen its audience more than double in the last two years. The way and places to distribute and consume media has been shifting dramatically.

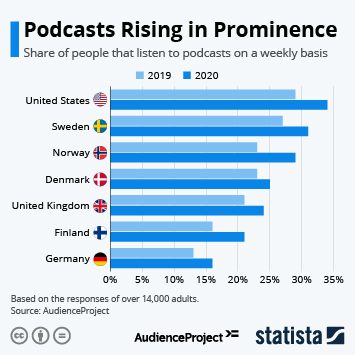

The continuing growth in podcasting

Podcasting in general has been growing around the world, as shown in the graph to the right. In the US, the Infinite Dial 2021 report showed over 17% growth year/year of adults who were weekly podcast listeners. But the US is certainly not the world leader in total podcast penetration. According to Statista, the US sits at 5th in world rankings at 33%, well behind South Korea at 53%. Surely, podcasting is no longer just an amateur media. It’s absolutely possible to make money, as shown by certain big name deals, e.g. last year, headlining significant transactions, Joe Rogan signed a $100MM multi-year deal to be exclusive to Spotify. I’m proud myself to have signed up with the Evergreen Podcast network with both of my own podcasts! Naturally, most mass media players have now gotten into the act. The question now becomes how we (and journalists in particular) seek out alternative voices to stay in touch and, thereby, help make better sense of what is going on?

The drop in trust…

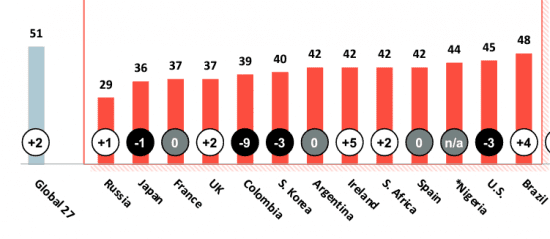

At this afore-mentioned event, I highlighted how public trust in journalists and journalism was low. I showed how, in 2018 according to IPSOS in the UK, journalists were rated at the same level as real estate agents, behind bankers and only 1 point above professional football players. The latest international numbers from Edelman’s 2021 edition global trust barometer speak to a persistently low level of trust in media in many countries. Compared with NGOs, government and business, media was again in last place among these four institutions. Among the 27 countries in Edelman’s survey, worryingly, the US, France and UK all scored below 50, which means a majority of those polled state they distrust the media.

Surely, the above stats reflect how some media companies have veered more toward audience-hungry entertainment and to turning profits. Of course, media is not operating in a vacuum. They need to be solvent. Without being sustainable, they serve no purpose. The problem is that they need to survive and for that they need our eyeballs and subscriptions. But only 1 in 4 people is described in the 2021 survey as having a good “information hygiene.” Edelman asserts that this information hygiene has four criteria:

- News engagement (i.e. how often you engage with the media)

- Avoid information echo chambers (i.e. seek out differing points of view)

- Verify information (i.e. avoid assuming what they read is true)

- Do not amplify unvetted information (i.e. avoid spreading misinformation)

So, the key message and responsibility is thus on each one of us to do better. Meanwhile, I would like to add two more criteria:

- Whenever possible, make sure your presence is nominative and verifiable, i.e. have the courage to stand behind your words.

- When evaluating the media you’re consuming, be aware of their editorial line and business model/financial owners.

Democracy in the balance

Across liberal democracies around the world, it feels like democracy is under stress. By its de facto nature, democracy is a messy, uneven system. But it’s not a birthright that we are guaranteed to keep forever, at least not without each of us playing our part.

Among the players responsible for protecting democracy, media obviously has a vital role. In a podcast interview I had with the reputed French journalist, Philippe Meyer, he pointed out that the media can’t make up for the lack of vision and character among politicians. Politicians have the front line role in maintaining the democracy while media basically is a buffer. However, just cancelling individuals and doling out insults — especially without proper foundations or facts — is no way to provide an effective buffer.

Legal and ethical frameworks

Alongside the presently divisive nature of politics, the rule of law has been weakened. Trust in the police and, more systemically, in the judicial arm has also waned. This recent article from Slate by staff writers, by Dahlia Lithwick and Mark Joseph Stern, describes the loss of legitimacy of the Supreme Court in the US. We need to be careful what we ask for when it comes to calls for total transparency, defunding police and a hyper focus on all minorities.

Politics without religion?

I am not a religious person. I’ve long wanted to find a broad-based ethical framework that doesn’t rely on religion as the ultimate authority. Yet, having authority is vital to corral the energies and unite the people. Among countries where religion and politics are readily intertwined, we see a confrontation of ideologies: as if my religion or God is better than yours. And, more worryingly, in the case of Sharia law, there’s an incompatibility with the existing legal framework of our established democracies. Whereas I favor the French “laicity” approach that makes a clear distinction between politics and religion, I also am in favor of nations being able to maintain a cultural heritage and identity, including, for example, recognizing one’s Greco-Roman and/or Judeo-Christian background. Importantly, I believe strongly that when you visit or move to a foreign land, you opt in for and accept the local mores, laws, language and customs. Of course, this isn’t meant to be a retrograde call to return to the way we were centuries ago. But it does mean taking a stand and being prepared to be different. It means defining who we are in the aggregate, where we are prepared to evolve and, more emphatically, what we’re not prepared to lose or change.

For each country, albeit differently, its constituents will need to lean into what it means to be a citizen of that country. What do we stand for? What are our non-negotiable values to which, as a group, we can all agree in our messy democratic way? And when we say we stand for a value such as freedom, what exactly do we mean? A freedom to believe, say or do anything? Or are there limits and contours to our specific values? This is a conversation I would love for the media to lead and to promote. It is in this context, I believe we all need to exhibit a greater courage — despite the fears and perils — to stand up for what one believes.

Media on Purpose – Finding a New North

Mainstream media’s purpose — and mission — has been diluted if not eliminated by the revolution of the Internet, where everyone has a soapbox. Serious media’s North Star should be to make sense of what’s happening, create platforms for more uncensored debate and establish with authority the facts. In light of the worrying level of censorship, cancel culture and questionable ethical practices at certain big tech companies (i.e. those identified by the recent Facebook whistleblowers, Frances Haugen and Sophie Zhang…), reputable mainstream media should lean into its most important purpose: to make sense of significant events and movements, bringing reasoned and researched authority to facts [and whenever possible truth], and to protect and foster a healthy debate. After all, we’ve seen how running after numbers (and profits) can corrupt one’s ethics.

The Future of Media and Why Mainstream Media Needs a New NorthSerious media's North Star should be to make sense of what's happening, create platforms for more uncensored debate and establish with authority the facts. Share on XFor the benefits of democracy, we can’t have universities and large mainstream media dictating a singular perspective. It’s time for mainstream media to step up to the plate and re-evaluate how its editorial line can be enlarged to accept healthier discussion around all sides of the key questions. I know that there are plenty of well-meaning journalists and I’ve been impressed by the spectrum of debate in titles like The Financial Times and The Spectator, even if left-leaning media will tend to scoff at some of their content. For the sake of protecting and making more robust our democracies, I hope that a few journalists will take note and lean into this vital purpose. [Addendum Oct 22 2021 in blue] I take this opportunity to salute Maria Ressa (who cofounded Rappler and whom I’ve had the pleasure of meeting two times) and Dimitry Muratov (Novaya Gazeta) who were awarded the 2021 Nobel Peace prize. It’s also worth pointing out that in 2020, there were 32 journalists killed with a confirmed motive according to the NGO, Committee to Protect Journalists. As the CPJ tallies, there have been 1418 journalists killed with a confirmed motive since it started recording the deaths in 1992 (with a peak of 76 in 2009). As Maria Ressa said in a recent Economist interview, “journalists are all on the same side: the side of facts.” Would that all journalists took that to heart — on both sides of the political spectrum. Freedom of press is vital for the democratic process. The meat of the question then boils down to how to define the outer extremities, that which is unacceptable. And here, we have a very real battle of narratives. We, as citizens, need to recognize our own role to have a healthier information hygiene and contribute to the discussion in our private spheres as well as in public.

Naturally, I welcome your comments, insights and rebuttals, hopefully keeping to the spirit in which this article was written.

Good stuff, Minter. I fear for our global media ecosystem, which now increasingly rewards mis/disinformation by design. Capital flows to media that practice simplistic rhetorical tools that exploit our society’s eroded critical-thinking skills. This is one of many overlapping crises I see for democracy and societal problem-solving. I’m afraid the ship will be slow to right itself, but perhaps your suggestion that the stodgy old MSM pay better attention to what the newer players are offering would help.

It will certainly be a messy journey, Van. I strongly believe that the new channels bear witness for the need for a different kind of media…

Great post Minter. I agree that we need platforms where views are not censored, rather pre-labelled as being extremely hyperpartisan, contradictory, inflammatory or one-sided, or not backing up statements with evidence. This way, readers can be warned about posts, and users posting can be nudged before they write things that don’t back things up. This is where AI can help and what Factmata, the company I founded, is working on.

Good to know we have tech initiatives looking at this very question Dhruv. Getting the algorithms to ferret out, with upstream objectivity, the misinformation and to verify facts without attention to “narratives” will be a core challenge I guess?

Great piece. You’ve hit the nail on the head in terms of journalists and all of us having to self-police more than ever before. It’s been said before but we’re all journalists now.

The volume of information and voices out there now is impossible to keep on top of, so I find it hard to blame journalists for not knowing the list of organisations and names you start with. I didn’t know any of them!

Separately, I would mention the decline of local newspapers, which is a little seen effect of the rise of the internet, but it’s had a great effect on the quality of journalism nationally in the UK. Local papers used to be an apprenticeship, where young journalists learned how to report on an event with impartiality, reliant only on the facts. That didn’t always happen, of course, but generally speaking regional newspapers produced a healthy tranche of trained reporters, who then went on to national newspapers, where they became national reporters, news editors and editors. That local paper apprenticeship is now diminished, because local papers have suffered so much since the recession of the early 2000s and through the impact of the internet on print advertising. Either regional papers have closed, or they’re so low on revenue that reporters are stretched to a point where training and quality suffers.

The prevalence nowadays of opinion expressed in news stories is one result. This is so casually done it’s often not noticed. I complained to the BCC over a story where they referred to QAnon as “the baseless conspiracy theory QAnon”. Regardless of anyone’s own opinions about QAnon, that is not a phrase any real reporter should be writing. They are free to quote someone else saying that QAnon is a ‘baseless conspiracy theory’, but expressing that opinion themselves is not objective, independent reporting. People will read what I’ve written here and think: ‘Yes but we all know Qanon is rubbish’. I agree it’s rubbish, but that doesn’t mean an impartial news report can simply say it’s rubbish. If they can, then they can say the same about something Joe Biden said, or about climate change, or about Covid vaccinations. You have to start with an impartial news report to regain trust in the press. You should never be able to read a news article and be able to tell anything about the author’s own feelings or leanings. Sadly, almost every news article today fails that test. That, mainly, is the ‘north’ that has been lost.

Also gone from the modern newsroom is the sub-editor – the fact-checker and the sense-checker, often the person who did the final polishing to ensure high editorial standards were met. The decision to cut sub-editors from newsrooms was a financial one, made by people who didn’t understand the sub-editor’s importance. Producing a reliable, trustworthy publication is not a one-person job. You need a team of people simply because it takes others to check your work.

If you’re looking for a new ‘north’ for all the media, print or broadcast, putting out impartial reports would be a good place to start.

What a lot of great insights, Rob. Absolutely gut-wrenching to see the decline of local press in light of the preparatory experience it provides for the national press. And, about the lack of the sub-editor too. This speaks to the broken business model that doesn’t allow local press to survive and has brought such pressure on the major titles to cut corners and costs that there’s no longer enough funding for the support functions or for sufficient investigative journalism. Hopefully, there are entrepreneurs who are looking at ways to use tech to compensate/strengthen journalism.

As you say, in reference to QAnon, we must find ways to talk about the facts without imposing our opinion, much less virtue signalling or self-righteous grandstanding. I so agree: journalists — and journalism schools — must reinvest into this North Star!

Many thanks for your thoughtful comment, Rob.