To avoid discounting product or potential flooding of the market, luxury brands have been to known to go to extremes. Burberry’s intentional burning of excess inventory this summer caused a big stir. {See the Huffpo writeup} Following a fairly common industry practice, Burberry wanted to avoid tarnishing its luxury stance with discounted outlet sales or, worse, distribution in the grey market. Even if most people “get” the idea of scarcity and the desire to avoid discounting, the volume of waste (£28MM’s worth of Burberry goods) raised alarm bells. The public outcry caused them to change their policy with immediate effect. Marco Gobbetti, Burberry’s CEO, said: “Modern luxury means being socially and environmentally responsible. This belief is core to us at Burberry and key to our long-term success.” On this I mostly agree. As Caleb and I wrote in Futureproof, responsibility is a key mindset for maintaining a healthy brand long-term. Yet, it is the ethical responsibility that seems to me most important.

The Luxury Performance

The crossroads — if not paradox — between chasing short-term results and keeping up luxurious appearances is a dicey path. At a practical level, luxury goods must be manufactured with exquisite precision and, essentially by definition, without huge production runs. Meanwhile, a business leader must link projected turnover with value of the stock produced. Most marketers would tend to prefer to have a little more than a little less stock because of the fear of missed sales. But, too much inventory is major burden logistically, not to mention for the brand image. For the luxury brand, it may be a marketing ploy to intentionally under-produce as part of scarcity marketing. As we know, once any luxury item becomes too available, its value wanes. The real trick is in creating pent up demand.

The Definition of Luxury

During my career, I have long puzzled over the fact that America is incapable of producing genuine luxury brands, at least none that is hyper luxury. Sure, there are a few brands, such as Tiffany’s, Donna Karan, Rolex and Coach, that could be considered as luxury, but very few US brands can claim being the epitome of sophisticated luxury. For example, Coach has 60% of its sales from outlet sales. Donna Karan has DKNY. Rolex is… well very Rolex. Among the more significant challenges is reconciling the need for performance (shareholder pressures) and the principle of scarcity. As soon as one privileges volume and top line sales, the lustre eventually diminishes.

The Luxury Chain of Value

In this multi-channel world, the notion of controlling your destiny has been thrown for a loop. People want convenience, no matter the positioning. Transparency on pricing has put renewed pressure on companies to justify their price policies around the world. As part of the new world order, it has become increasingly important to figure out the right collaborations and partnerships. This is in part because of the plethora of new technologies and opportunities that require alternative expertises that may not reside in-house. It’s also a question of choosing the right distribution partners. The Internet and eCommerce can quickly shine a light on inconsistent — or poor choices of — partners.

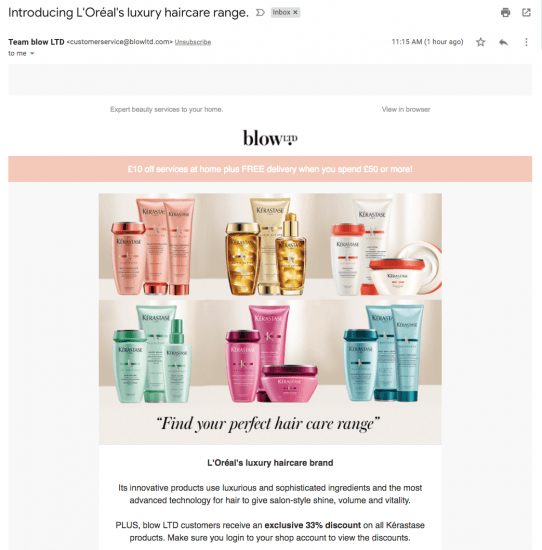

L’Oreal, a company I know well for having worked there for 16 years, has a entire Division called LUXE and, for some of the brands in the portfolio, they do verge on luxury. They also have a few upscale brands in the Professional Products Division, where I spent my entire career at L’Oreal. One such upscale brand is Kerastase. With the entry level 250ml shampoos priced at £19.50 in the UK (20E in France or $30 in US), one might call Kerastase accessible luxury in terms of its price point. Over the last few years, meanwhile, Kerastase has become more available online. But it doesn’t take long to see how the brand has a mixed positioning. Its partnership with Blow Ltd (see below) has produced a number of legitimate discounted product.

As a result, I have quibble with the title: L’Oreal luxury haircare brand, as written on the Blow site. Providing a 33% discount is a symptom of a mass market mentality.

The signals of true luxury are often in the details. Luxury is an intangible aura. But when you lose control of the pricing, come under sales pressures and/or find the wrong partners, the luxury sheen is torn off quickly. Does that mean that the brand won’t be successful? Maybe not. It’s a lovely brand. But it shouldn’t pretend to be luxury.