In the beauty business — just as in any FMCG sector, be it food, fashion, household care or appliances — there is a handful of multinational conglomerates that each own a whole corpus of brands, most of which compete with one another. To the extent a conglomerate owns many brands, it stands to reason that it must find a way to create superior added value versus the independent brand. Whereas the conglomerate will be providing R&D muscle, international reach as well as leveraging its buying power (with distribution) and economies of scale, it is also inevitably fettered down with bureaucracy (process and policies), internal politics and legacy systems. Among the strongest suits a conglomerate can play is the chance to share and learn from each of the brands. Share on X However, the parallel risk is the inability to separate the brands and to keep strong independent brand territories.

The Federating Beauty Portal

It is in this context that I wanted to address the notion of a federating beauty portal for the beauty conglomerates. For most independent brands, because of scale and focus, they are typically obliged to intermingle their content within their brand site. For the conglomerates, however, there is an opportunity to create a supra-site that talks to the beauty category as a whole. It is an alluring concept because it means that the conglomerate is “capturing” the conversation that just will not happen naturally on their own site. Theoretically, it creates a favorable environment to engage with a broader customer base. It also justifies headquarter’s existence. For the top 3 major beauty conglomerates, each has been seduced by the idea. I’m not convinced that the consumer has been so lucky.

L’Oreal focus on makeup

L’Oreal

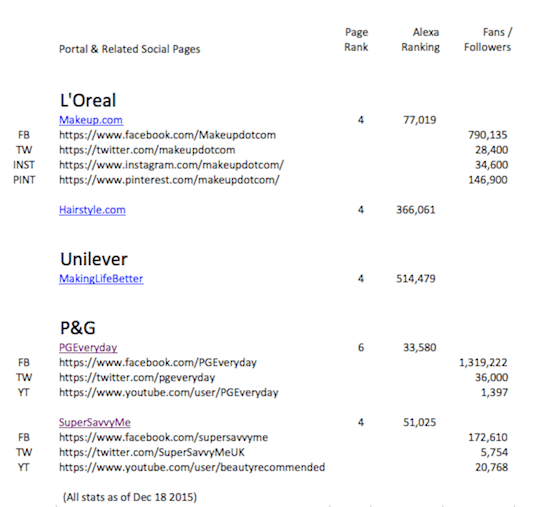

, with $27.4 billion in sales in 2014 (source), is the #1 beauty business. With its four different divisions (plus The Body Shop), L’Oreal has been actively acquiring brands — including Magic, NYX, Carol’s Daughter, Decléor, Carita and Niely — to complement its portfolio of 32 international brands. L’Oreal launched in July 2010 its beauty portal focused on cosmetics: makeup.com. Initially set as a blog, it has evolved over time, and can be considered an online publication, sourcing content from an editorial staff and a network of vloggers. Makeup.com covers, of course, only products in the L’Oreal portfolio. In one click on a product reference, you are sent to the corresponding eCommerce site.

SOCIAL FAUX PAS – On the positive side, makeup.com has a surround sound social strategy, with dedicated pages on Facebook, Twitter, Youtube and Pinterest. However, I note that when looking at the execution on Facebook, it is not hard to be critical of their editorial line and a distinct lack of engagement. The social team has a habit of posting up to 6 posts every day on its Facebook page (pounding them out from 5pm onward). Engagement is predictably miserable considering the 790K “fans”. With that number of disengaged fans, one has to question how they came upon such a large “following.” On Twitter, the account has a one-way attitude: multiple tweets each day with only makeup.com content, without the slightest conversation or exchange.

N.B. In 2013, L’Oreal Paris also launched a portal around hair, called hairstyle.com (still operating for the North American market) and rolled it out into five countries.

Unilever – Making Life Better

Like L’Oreal, Unilever ($21.5 billion in beauty sales in 2014, out of a total of $58.8B) has been an active acquirer, picking up in the past year, among other brands, Camay (from PG), Dermalogica, Murad, Kate Somerville and Ren. The MakingLifeBetter portal (UPDATED: now defunct) includes Unilever’s food brands and has a tab for Experts, featuring individuals (or duos) for food, beauty, hair, family & nutrition. On the positive side, the title (ambition) of Unilever’s portal is missionary: to make life better. Interestingly, however, Unilever has not supported its MakingLifeBetter with a dedicated social media strategy. The social buttons only point to Unilever’s corporate social sites. A major faux pas: it’s not mobile friendly. In 2015, that’s a no-no. In 2016, that’s a disaster.

Procter & Gamble – Everyday

P&G has divested a large number of beauty brands recently. As a result, it has slipped back to the #3 beauty company worldwide, registering an adjusted $18.1 billion in beauty sales in 2014 (out of a total of $76.3B). Albeit encompassing the full range of the P&G product range and brands, the PGEveryday site has a very generic “template” feel to it. By putting P&G — which is not a commercial brand — in the URL, the federating theme of the site is decidedly corporate. As such, the site lacks cohesion or purpose, from the consumer’s perspective. The make-up tips section is a hodge-podge collection of posts from a variety of sources. On the far right tab, PGEveryday has an elaborate way to get coupons and offers (perhaps very American in spirit). The supporting social media is dedicated and has a larger following than either L’Oreal or Unilever. On Facebook, in particular, engagement is significantly higher than on makeup.com, indicating a better style and rhythm of posts.

As an example of a global initiative that has been localized, the P&G UK team has taken the US framework and re-positioned it around the theme SuperSavvyMe, which avoids naming the P&G corporation directly in the URL. Rather than having coupons, this version prefers to offer “exclusives and rewards”. In the UK version, Beauty is relabeled as “Beauty Recommended” for which the UK have a dedicated set of social media sites. The wording is more customer friendly than on the US version.

Beauty Portals – Where is the Conversation and Engagement?

Overall, all three companies have very different executions, with very different social strategies. L’Oreal’s makeup.com is focused on a single area (cosmetics) and certainly has the most attractive UX. If the Alexa ranking for makeup.com is still a little behind P&G’s sites (see below), it has a better overall approach. P&G and Unilever’s portals aggregate brands that cover health to beauty to household care, etc.. In both cases, the scope seems too wide to gain a concentrated following. Whereas I have not evaluated the quality of the content on each site, the challenge is to find an appropriate line between editorial and helpful content with the urge to sell product.

Gaining fidelity in a beauty portal

The conglomerates are not alone in trying to “unite” consumers under the beauty banner. The major distributors and media companies are equally anxious to federate the beauty conversation. There are also individual efforts — unfettered by corporate ethics and/or shareholder pressure — that exist and carry a certain attraction because they are independent, authentic and non commercial. The authors of these sites are able to critique products openly and thus earn more credibility and trust from their viewers. They build true fidelity. The most successful of them are individual vloggers; but as they get successful, there is the lure/need of a corporate sponsorship. When these sites gain traction, it is entirely predictable that they will be in turn consumed (i.e. acquired) and swayed by the same temptations and pressures.

In conclusion…

Getting any portal, much less a beauty portal, to work is no mean feat. It requires strategy, resources and long-term determination. From a business standpoint, the portal’s success should be gauged against the company’s objectives. However, taking an outside eye, real success is measured by the engaged community. Portals underwritten by an institution (e.g. a corporate conglomerate) have an inherent built-in distrust, for which the manufacturers need to compensate. Some of the keys to success lie in working with influencers, creating a relevant eco-system on social media, offering a good user experience (especially on mobile) and finding an authentic and engaging content.

A beauty portal should be more about beauty than brands, community more than commerce and content more than conversions. Share on X