At its core, branding is about adding value into one’s offer. It is both an art and a science. The science is typically applied to innovation in the form of Research & Development, the excellence in the product and the veracity of the claims. But, there is also the science of media buying, the way the product is arranged on shelf, field research and more. Once the value-added is reflected in the set price, there is, of course, the issue of economics and the science of supply and demand. In terms of the art of marketing, there is the magic of storytelling, the creativity in the advert, the mystique in the secret sauce, the chemistry with the sales team, and so on.

All that being said, when the value-added component is not evident, i.e. it is not easy to explain, the floor on the price can quickly disappear. In today’s world, where transparency is increasingly the norm, the justification of a high price can become an issue of public debate and a juicy object of media investigation. {Tweet ♺}

Exposing the truth

A recent investigation aired in France, by the publicly owned France2 television station, on cosmetics pricing really intrigued me. The program, entitled a Special Envoy, tackled the difference in performance (and safety) between low-cost and super premium/luxury products. On the one hand, the conclusion of the report (which is embedded below and, I’m afraid, in French) was scathing about the objective performance of the products. On the other hand, it’s worth also noting the station chose not to identify the brands being evaluated. Unless you have eagle sharp eyes and are a bit of an investigator yourself, you won’t know which are the ‘expensive’ ones that underperformed so dramatically against the cheaper options. No doubt, the items were carefully selected for the outcome. However, the reporter has established scientists verifying the results.

“ENVOYÉ SPECIAL du 14 mai 2015 – La Beauté à prix low cost” (in French)

Value-added versus low-cost

The programme went to great pains to hide the name of the products being tested. Perhaps the point was to avoid the polemic on the exact brands, and to surface more the issue of price gouging? In any event, they tested cheap versus expensive make-up and skin care. They could very easily have done the same with hair care, I would add. The three skin creams, ranging from 3 euros to 65 euros, all came in 50g jars in a box, so they did make attempts to equalize the competition.

Value added innovation?

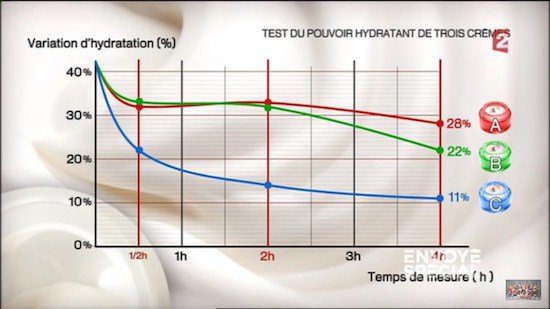

The highlight results showed that, over a four-hour period, the hydration level for the cheapest (A) was best, second best was the second cheapest (B) and was least effective for the most expensive cream (C), which was a Chanel cream.

With my experience at L’Oreal, I can imagine the type of rebuttal that could be made, including “Ah, but our cream is for a more mature skin than the model in the program…” Nonetheless, this type of report does undermine the value of high-priced cosmetics. For employees working on value-added products (i.e. where pricing is high), it can also be a gut check, whether “I’m worth it!“

Value must be added in a trustworthy manner

So, the challenge for brands that are selling products whose cost of production is a tiny fraction of the final consumer price, will be faced more and more with justifying the higher price. To the extent the larger multinational cosmetic manufacturers consistently look to cut costs, synergize their back-office departments (including laboratories, innovations and ingredients) and run a portfolio of brands, the transparency that the Internet affords will create some unhappy moments. For most consumers, this information remains as yet vague. For example, how many customers are fully aware that L’Oreal owns Lancome and Maybelline? The truth is out there.{♺} I found this commentary online (site taken down) from a former L’Oreal employee:

As a makeup artist who … worked as both a makeup artist and business manager in the NE region for Lancome, I can honestly say that the products are not worth the money. Many of us were told, right at our early trainings that L’Oreal owns and makes Lancome and that several products are essentially the same. This is not just an opinion–if you compare the ingredients you will find that many are identical, with the exception of a dye or fragrance component.

As the anonymized person — who also used to work for a large cosmetic company — reports toward the end of the Special Envoy report: the cost of R&D in the final product is insignificant. It’s all in the advertising. And when 2 million euros per year are being siphoned off for celebrity endorsement, the value-added put into the product can, finally, seem rather hollow. It all amounts to rather shallow marketing and a lowering of trust in the consumer (and employee’s) eyes.{♺} In this evermore transparent world, marketers will inevitably have to redouble their efforts to find ways to make the value-added substantive and worthwhile.{♺}

If you are looking for an interesting alternative source about cosmetics, in terms of their carcinogenicity, toxicity and allergens, you should check out ThinkDirty, an app created out of Canada, that gives a scientific review of the ingredients of nearly 300K products, as well as bringing in consumer reviews. Definitely worth the download if you are a frequent consumer of cosmetics, or even work in the business! It’s just another example of how transparency is creeping in to every business.

Your thoughts and reactions?