The average lifespan of a publicly traded company continues to fall. Depending on who you listen to, the number is now below 18 years. That number has dropped from 61 in 1958 and 25 in 1980. That’s what was reported in this 2012 Innosight study. Richard Foster, a lecturer at the Yale School of Management, has declared that the lifespan is just 15 years today and that at the current churn rate, Foster estimates that 3/4 of the existing S&P 500 firms will be replaced by new firms by 2027. As Dominic Barton, Global Managing Director at McKinsey stated, every two weeks, a company on the S&P500 is disappearing from the list.

In a conversation I had with my pal, Mitch Joel, we jousted over the relevance of that lifespan number. That got me thinking about perspective.

How long is long?

Here are some different ways one can view that 15 to 18 year number:

- As an entrepreneur (a startup), you’d be laughing (because so many startups languish or die within 3 years). Anyway, depending on your ambition, you hope to be long gone?

- As a founder with an ambition of legacy, perhaps that’s not very encouraging, especially if the company is in your name.

- For an employee, it depends on whether you think you’d love to work at that company for a good portion of your eligible working lifespan.

- For a toddler, that’s an eternity.

- For a Gen Y or Gen Z, the question is probably WTFC*?

- For an equity’s analyst, that’s well beyond any reasonable stock market time horizons.

- For a new current shareholder, that’s plenty of time to make lots of money.

- From the perspective of an longtime shareholder, perhaps they are wishing for the buyout at a premium?

- For a trader, you’ll have an easier time explaining the merits of a 5-day cricket test (between two far away countries).

- For the current CEO, that’s three or four CEOs after him/her.

- …

Bottom line, the fact that company lifespans have declined so radically doesn’t really impact many of the people in the list above. However, there is one profile in the list above with whom I relate a lot: the ambitious founder. If you’re going to go out on a limb and entreprendre the risk of starting a company, it is more like giving birth to a child. You’d probably rather not see it die as a teenager.

The Natural Cyclical Lifespan

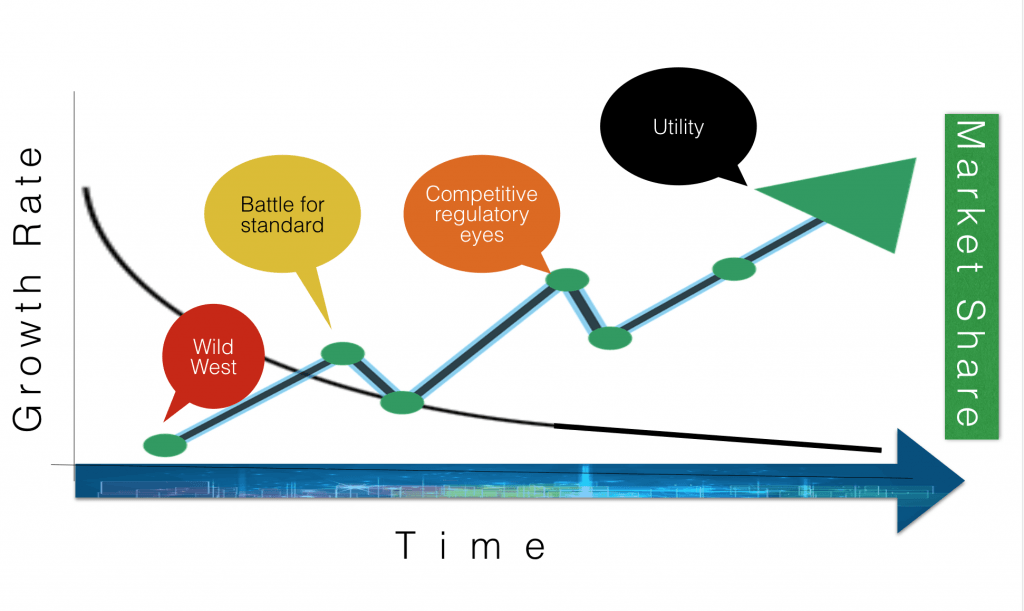

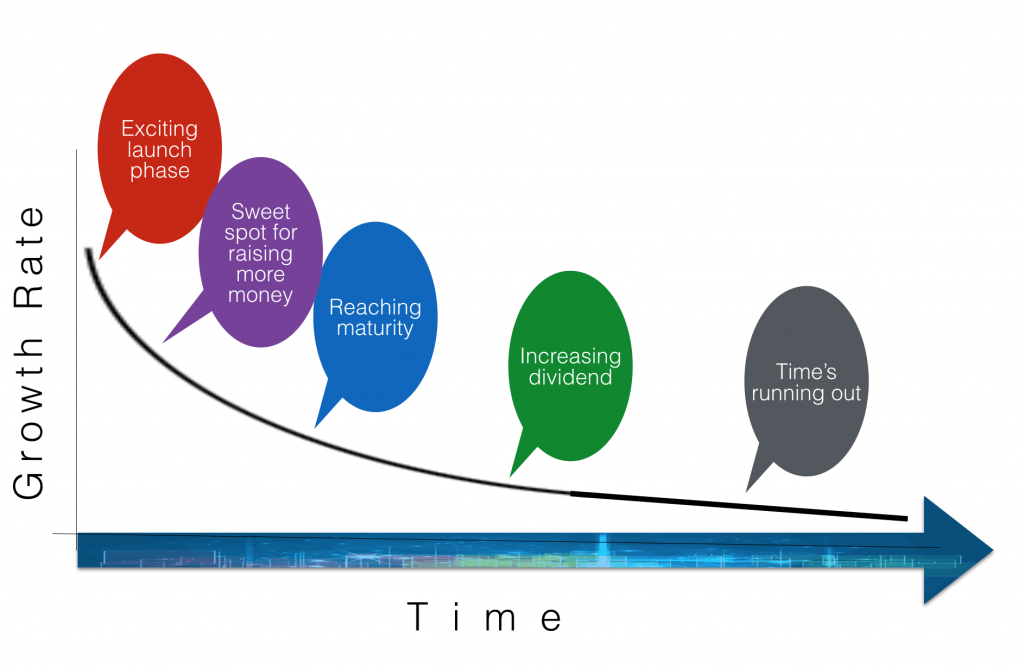

At the beginning of life for Peugeot, L’Oreal, Starbucks and others, there were individuals who created a company whose longevity was anything but guaranteed. They have now acquired the seeming status of “permanent,” with a regular presence in our vocabulary or psyche. However, depending on the industry, there is a repetitive cycle, where the real variable is the length of time. And for each, there’s a limit. There is a general inevitability to the fall in growth rate and an evolution in the perception of and expected returns for the shareholders.

All that for this?

All that for this?

As we are all battling and busting our butts for better sales, increased margins and, eventually, higher market shares, the perspectives of each other are a certain form of reality. The salient point in the less-than-18-year horizon is that these figures are for publicly traded companies. For those that have the ability to auto-finance and stay private, the implicit desire is generally to survive longer than just one 15-year cycle. Moreover, their data is not readily available, anyway. Whether private or publicly traded, the ability to grow market share indefinitely is bound to hit roadblocks, including regulatory oversight and government intervention. If a dominant market share persists, the chances are that it will ultimately end up as a utility…. What does the future of a Google hold? Obviously, there are many different scenarios. But, the reality of the shorter lifespan of a publicly traded company is also a function of the changing tech environment, not to call it directly: the new tech revolution. A slug of the disappearances from the S&500 are good news, at least if you look at it from the recent shareholders’ perspective (i.e. when it’s an acquisition). But for many, it’s because the company didn’t know to survive alone. As a result, bosses are re-quartered. Jobs are affected. Brand names change. Cultures evolve. Businesses disappear and others spring up. Thrive or Die. As Caleb and I like to say, companies need to futureproof themselves in mindset, first.

Obviously, there are many different scenarios. But, the reality of the shorter lifespan of a publicly traded company is also a function of the changing tech environment, not to call it directly: the new tech revolution. A slug of the disappearances from the S&500 are good news, at least if you look at it from the recent shareholders’ perspective (i.e. when it’s an acquisition). But for many, it’s because the company didn’t know to survive alone. As a result, bosses are re-quartered. Jobs are affected. Brand names change. Cultures evolve. Businesses disappear and others spring up. Thrive or Die. As Caleb and I like to say, companies need to futureproof themselves in mindset, first.

The lifespan counts to the customer?

But, what of the customer’s viewpoint? Does it matter that the company is no longer around? You bet. From a practical standpoint, the lifetime guarantee goes out the window. Beloved brand names disappear. Any long-standing relationships are vaporized. And replenishment purchases are no longer possible.

If the decline of the lifespan of a company is not a concern for many of the people in the list above, I would argue that it is of grave consequence, not least because it is just an average and, for some companies, the end may be much closer than expected. As employers, even if prospective employees don’t all want to stick around for too long, we should be hoping to offer employees a career to capitalize on their talent and engagement (not to mention the cost of recruitment and training). As customers, the trust that lies in your brand is definitely impacted if your company is about to fold or disappear. So, as a leader, what is the time horizon of your true strategy?

Your thoughts?

*WTFC – the W stands for Who and the C for Cares.

All that for this?

All that for this?

Surely the average lifespan of a publicly listed company is reducing because companies are growing at a quicker rate and get listed quicker than they used to. This means that we have more and more younger companies. We also have a situation where increasing M&A activity at a larger scale and even re-privatisation could result in companies no longer being listed but essentially remaining in business. It doesn’t necessarily mean that publicly listed companies are failing earlier in their life.

My company is 10 years old and, thankfully, there is no sign of an IPO just yet…

The reasons for churn in the S&P are indeed varied. You’re right that many have fallen out because of faster growth by others. But, if your business doesn’t show the returns, it won’t get the capital as easily/cheaply and therefore will be forced onto another trajectory, including not having the resources to build new systems. invest in R&D, hire the best talent… etc.

The idea of self-funded growth takes all its glory when you don’t have to be beholden to short-term pressures that might make you take short-sighted, ethically questionable actions…. The notion of legacy for the founder is an important one, not just from a financial gain standpoint, but it looks to the “why” we are doing what we do. The more leaders look at the way they run their company — not just the results — the more they will be encouraged to review some of their practices, enhance employee engagement and, ultimately, capture the customers’ hearts as well as their pocketbook. With all the new tech in the pipe, it will be easy to take some questionable shortcuts because there are no legal frameworks to guide us. It will be up to the individual(s) leading the company to consider his/her personal ethical line.

Is does not have to be an exclusive choice of achieving your bonus versus leaving a powerful lasting legacy. I believe there are ways to do both. And, to my reckoning, it starts with the why you’re in business.